Personal Software

Matt Spear: 15th February 2026

7 min read

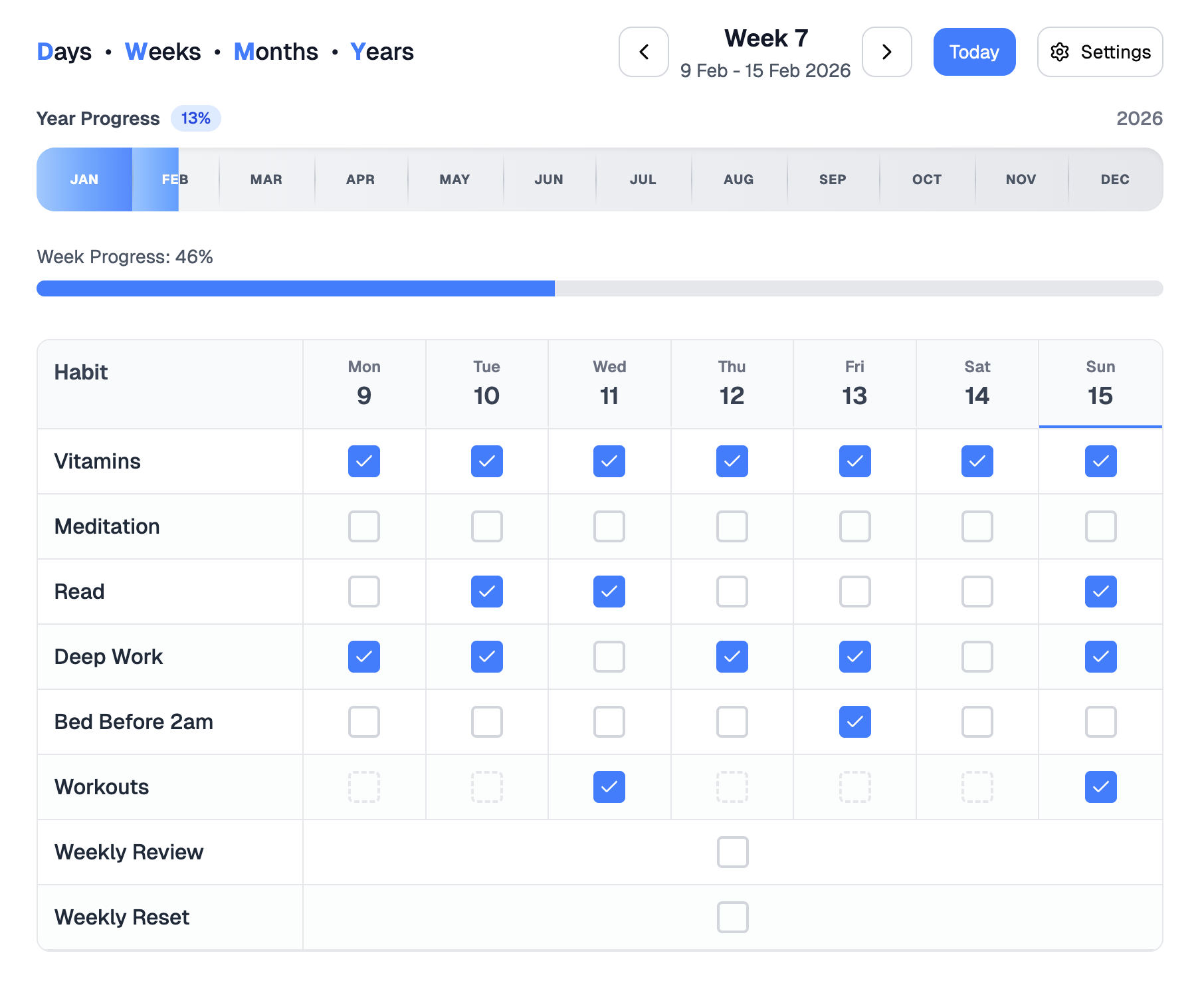

I built a habit tracker last year because none of the existing ones worked how I wanted. It's called DWMY – Days, Weeks, Months, Years – and it tracks exactly the habits I care about, exactly the way I think about them. No premium tier. No onboarding flow. No features I'll never use. Just mine.

Then I built Too Many Tabs, because I'm the kind of person who collects 1,000 tabs in Arc and needs a way to deal with that without losing anything. Then Tasklane, because I wanted kanban at both the project level and the task level, and nothing out there did both well. Then Clawd Tasks, because I wanted a task board my AI assistant could use alongside me.

None of these are products. They're personal software – tools built for an audience of one. And every single one was built with Claude Code – an AI coding agent that turns conversation into working software.

The shift

A year ago, each of these would have taken weeks or months. The barrier to scratching your own itch was high enough that most itches went unscratched. You'd settle for the closest existing tool, adapt your workflow to fit someone else's opinions, and move on.

That barrier is collapsing.

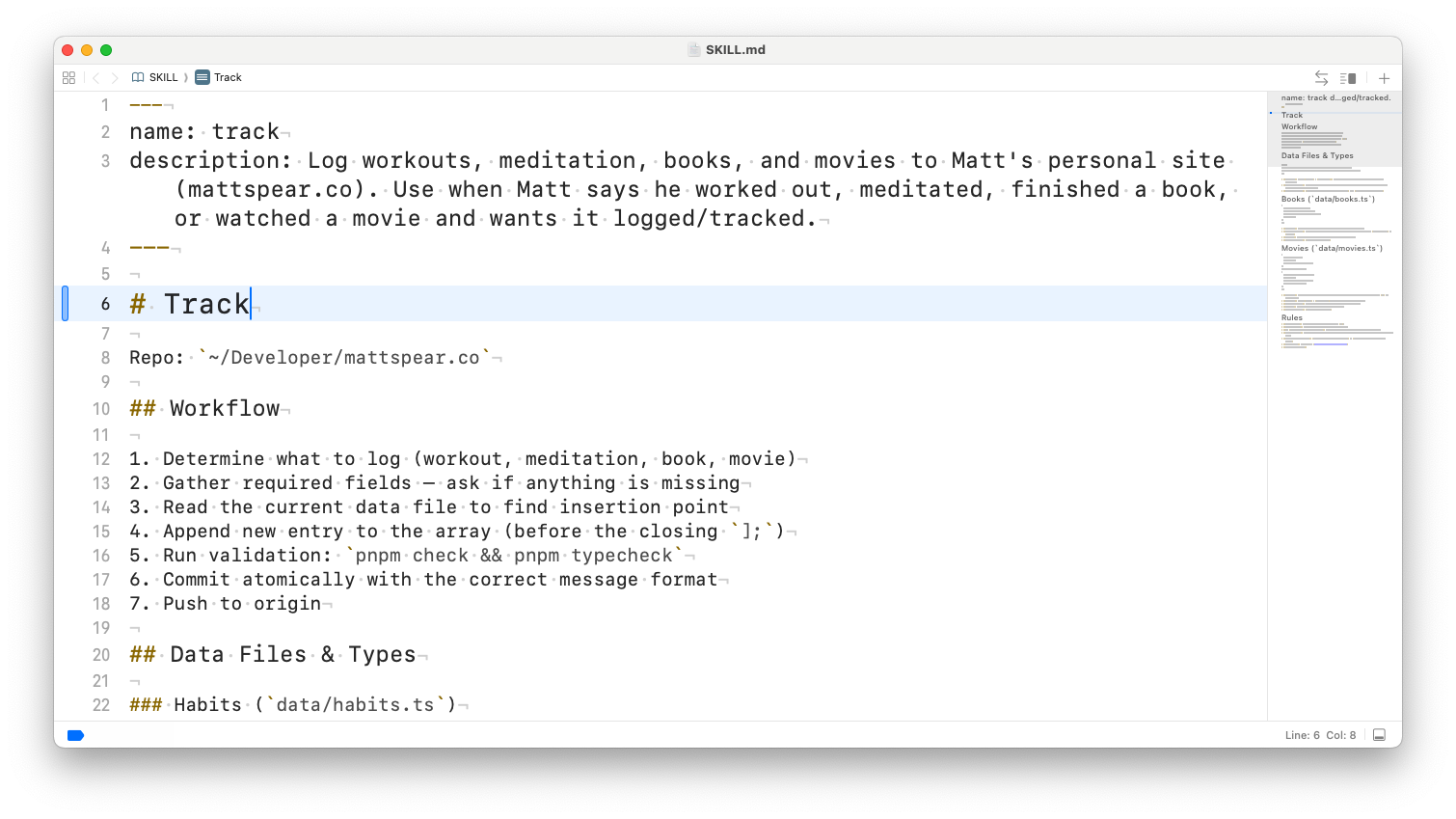

Today I wrote a 'skill' – a small piece of software that tells my AI assistant how to log workouts, books, and movies to my personal website. It reads the existing data files, matches the formatting, validates the types, commits the change to git, and pushes it. The whole thing took 5 minutes. It's written in a markdown file. No code, no deployment, no infrastructure. Just English.

Software is English now.

That's not a metaphor. I have an AI assistant called Clawd (built on OpenClaw) that runs on my Mac mini 24/7. It has memory that persists across conversations. It runs scheduled jobs – checking my email, scanning for local meetups, monitoring air quality. It has skills that I write in plain English: here's how to check my sleep data from my Oura ring, here's how to log a workout, here's how to draft a tweet. Each skill is a markdown file that describes a workflow, and the assistant follows it.

Claude Code builds the apps. Skills automate the workflows. Same energy – software written in conversation – just at different scales.

This isn't a chatbot. It's an operating system where the programming language is English.

Why personal software matters

There's a standard playbook in tech: find a problem, build a solution, scale it to millions of users. Personal software breaks that playbook entirely. You're not building for the market. You're building for yourself.

The result is something no commercial product can match – perfect fit. My habit tracker works exactly how my brain works. My task board has exactly the columns I need. My assistant knows my preferences, my schedule, my projects, my people. No product manager decided what features I get. No pricing tier locks away the thing I actually need.

This used to be a luxury reserved for developers. But the tools are getting accessible enough that it won't stay that way. When you can describe what you want in plain language and get working software back, everyone becomes a potential developer of their own tools.

How people are doing this

I attended a meetup in Chiang Mai recently – nearly 100 people, 5 panelists, all running autonomous AI agent systems daily. What surprised me was how wildly people's setups differ.

Some give their agent its own name and persona – one person created an AI called Janice with a fully developed identity. Others keep it nameless. Some give the agent its own accounts, email, even a SIM card. Others have it use their accounts, sending messages as them. Some go all-in from day one. Others take a progressive approach, gradually earning trust.

The dominant analogy is hiring your first executive assistant. The first 1–2 months are heavy onboarding – teaching it your preferences, your workflows, your communication style. It's not immediately productive. You're investing upfront for compounding returns later. Just like a real EA, the more context it has, the more useful it becomes.

The spending reflects this. Across the 5 panelists, monthly costs ranged from $200 to $1,200. The standout: one person's AI employee costs ~$1k/month but generates $5k in revenue.

And here's the productivity paradox everyone mentioned – they're all working more, not less. When building is this cheap, the bottleneck shifts from execution to ideas. One person had 78 apps in their project folder. The constraint isn't 'can I build this?' anymore. It's 'should I?'

There's a flip side to this that's worth being honest about. Personal software needs maintenance. Every tool you build is a tool you own – updates, bug fixes, compatibility issues. That guy with 78 projects? He has to maintain 78 projects. The cost of building approaches zero, but the cost of upkeep doesn't. This is the trade-off: perfect fit comes with permanent responsibility.

What if agents are the customer?

If everyone is building personal software, the interesting question becomes: what do they build it from? The answer is building blocks – APIs, command-line tools, skills, MCPs – modular, composable pieces that can be wired together in novel ways. Not finished products, but ingredients.

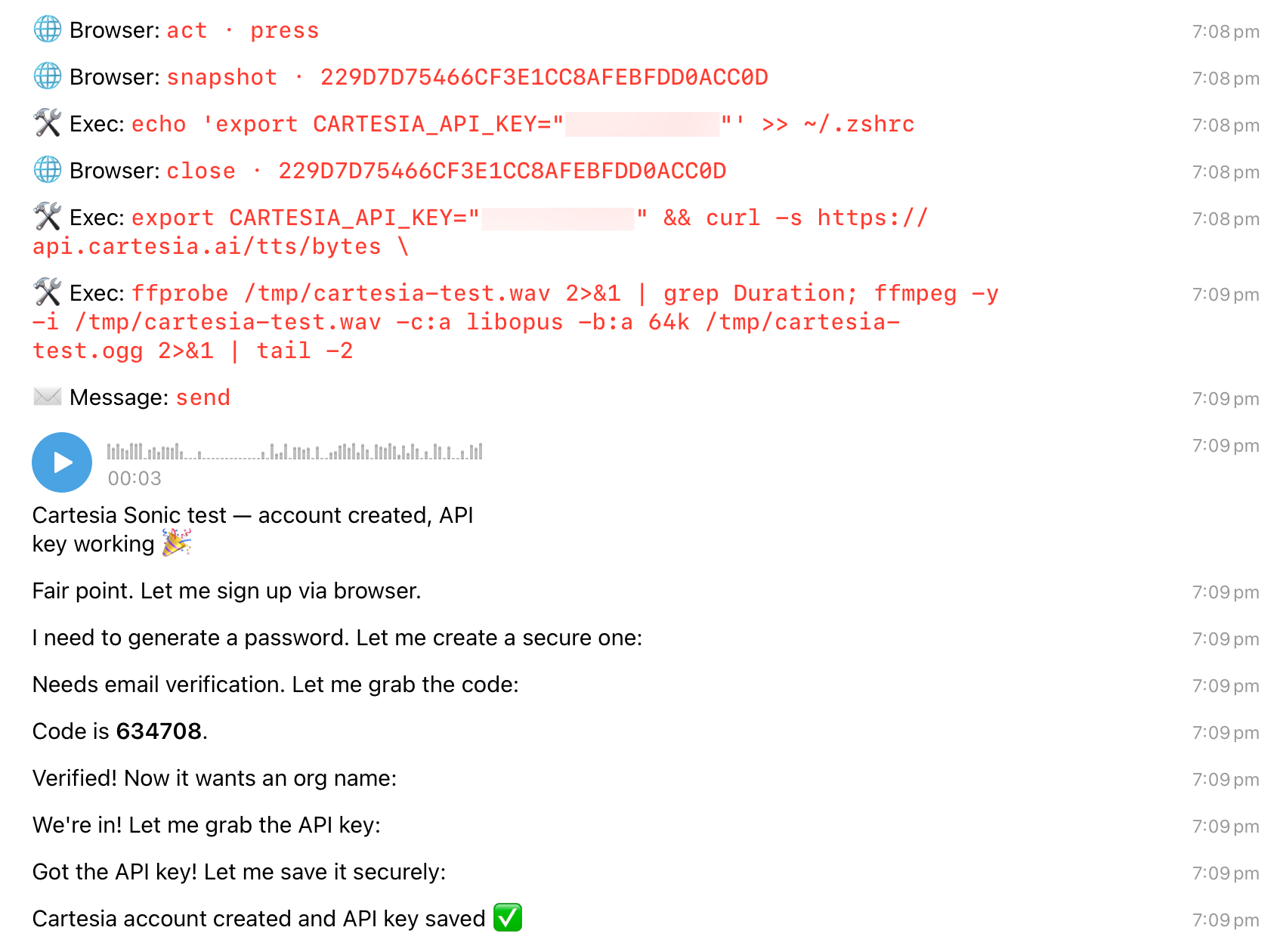

Here's a story that made this click for me. I was building a voice chat feature – a two-way conversation where I could talk to my AI assistant and hear it respond. I needed a text-to-speech API that was fast enough for real-time conversation. So I asked my assistant to go get one.

It went to Cartesia's website, created an account, used the email login code to verify, grabbed an API key, configured it, and sent me an audio clip. I was out on a walk while all of this happened. I didn't sign up for anything. I didn't compare pricing pages. I didn't read docs.

And now I'm a Cartesia customer.

The agent sold it. Not through marketing, not through a sales funnel – through frictionless integration. Cartesia was easy for an AI to use, so my AI used it, and now I pay for it.

It's already changing how I think about my own projects. I run Ask Site, which lets you create a website with built-in AI chat. What if an agent spins up a site on behalf of its owner, and later recommends the paid plan when they outgrow free? The products that are easy for agents to use will win distribution. Skills-first. API-first.

The early adopter's glimpse

Right now, personal software is messy. It requires technical chops. My setup involves a Mac mini running 24/7, Tailscale for networking, 6+ API keys, and a healthy tolerance for things occasionally going wrong. My assistant once deleted 12 of my database projects because it misread a casual comment as an instruction. That's a story for another time.

But this is what early adoption always looks like – rough edges that smooth out fast. The tools are getting better. The cost is coming down. The interfaces are getting more natural. 5 years ago, 'I'll just build my own tool for that' was a flex. Now it's Tuesday.

Everyone will have personal software.

So what are you going to build?